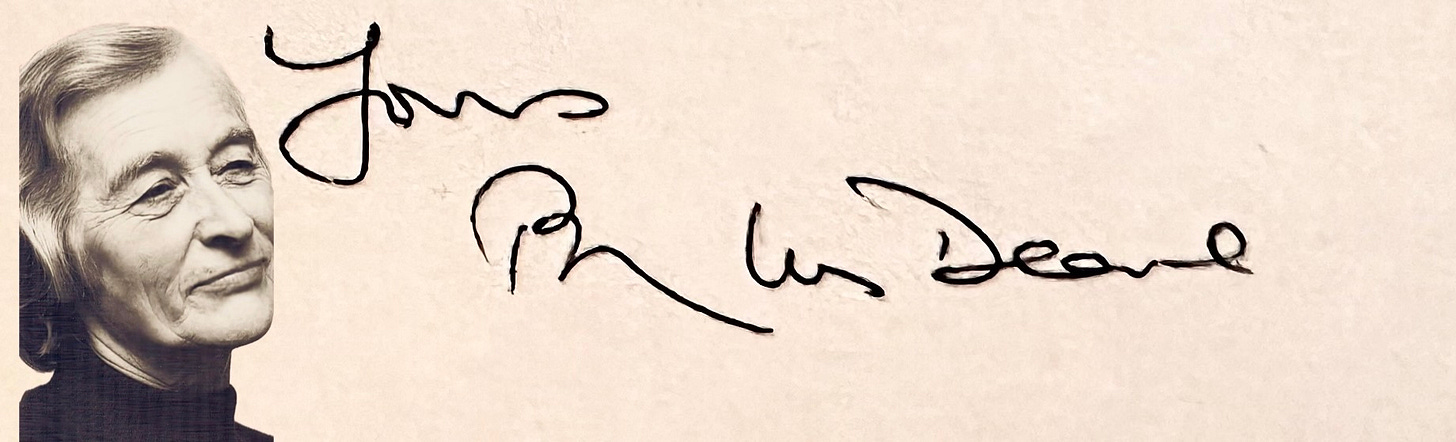

I have to admit that my first, and erroneous, impression of Phyllis Deane (1918-2012) was from her lectures, in my first year, on the Industrial Revolution. There was loads of content of course, but they seemed to send the clock to sleep. It was easier to read the book1. But looking back that classic book had come from those very same lectures, it was first published in 1965, reprinted in 1967, 1969, and 1974. And then, in 1975, she was giving them again, so perhaps there was an excuse for a lack of immediacy even if the lecture timetable slot was now shared with others. Apparently the University Press had sought in vain for an updated version2: she had moved on, also now lecturing on economic growth and the evolution of economic ideas. Of course, her work with W.A. Cole on historical growth figures was seminal3. At the same time Charles Feinstein4 and Robin Matthews5 were continuing their own work in the same area. It had become possible to do the same economic analysis of the industrial past as it was to consider the current economic state from the latest official national statistics. Phyllis had played a role not only in the development of national accounting but also in questioning its limits. This I would only learn much later.

National Income accounting, now so familiar, had come into being in two strands in the 20th century. The earlier strand came from the American Institutionalists studying business cycles6, culminating in Simon Kuznet’s work at the National Bureau of Economic Research. The second strand was from Keynes in the late 1930s and postwar period in the UK. The UK’s National Institute of Economic and Social Research had funded the completion of A.L. Bowley’s work on The National Income Enquiry in 1940, the following year Richard Stone and his research assistant Renée Hurstfield started working on “National Consumption and Expenditure 1920-38”7. Under another Cambridge economist, Austin Robinson, the project was expanded to apply the same principles to the British Colonies. Phyllis Deane, then only 23 and in her first job after graduating from Glasgow, was assigned to the task8. Her first visit was to Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), the project extended to Nyasaland (now Malawi) and Jamaica.

Phyllis soon recognised two significant problems. The first was how to value subsistence farming and other similar production in the home or community. The work done, largely by women, was often overlapping. She could estimate some things, like rug weaving or brewing beer, easily enough but others, such as collecting firewood and water, or transporting crops, were much less tractable. For much of this production there were no prices, and no detailed figures for their consumption either. What reliable data there was came from import and export data, or income tax returns of the largely expatriate community, not the indigenous population. A further problem was that, due to colonialism itself, the nature of foreign capital versus domestic was hard to define.

Despite the lack of data, her preliminary studies could show some important trends, for example which industries were more or less resilient in the face of a depression. However whilst this might illuminate current trends, trying to extend the analysis back in time was hampered both by the paucity of the data and the structural shifts occurring in a developing economy. All was not lost, however, relatively few data series were required to provide a more robust basis for future analysis; employment and wages, indices for output, sales and prices. The Jamaican economy fitted the national income accounting model quite well, though making international comparisons remained difficult because of the different structure of national economies. Africa was much harder, not least because much less was known about the social and economic structure, whilst colonialism meant that the total value of activity within the country was substantially different to the income earned by its nationals9.

The debate about what GDP should or should not value has continued ever since. If you employ a cleaner or a nurse then that contributes to national income, but unpaid housework or caring does not. Taking public transport to work gets included but cycling there does not. Phyllis, herself, continued to examine ways to quantify some of these things in a colonial setting, especially women’s work, publishing her further research in the early 1950s.10

In 1950 Richard Stone invited Phyllis to join him at Cambridge’s Department of Applied Economics. The DAE had been formally established in 1939 to foster economic, and particularly statistical, research. The war had intervened and Stone was only appointed as its first Director in 1945. Her work at the DEA led to the publications with Cole and Mitchell on the quantitative basis of British growth that marked a new era of British economic history11. It placed her in succession to Gregory King (1648-1712), one of the first great British economic statisticians. The department ran alongside the faculty, and so gradually Phyllis was drawn in to teaching as well as pure research. She was appointed Lecturer in Economics in 1961, also becoming a fellow of Newnham College, Reader in Economic History in 1971, and Professor of Economic History in 1981. She officially retired in 1983. She was an editor of the Economic Journal from 1965 to 1975, and President of the Royal Economic Society in 1980-82.

In the mid 1970s she turned towards the history of economic thought and methodology. As my own research work involved both, it was perhaps inevitable that she would be asked to cast her penetrating eye over some of these aspects. As a result she became a second and hugely valued supervisor. If a draft chapter could pass muster with Phyllis too, then surely it had to be OK. We dabbled in other interests too, both joining a small society for the history of the university. Her The Evolution of Economic Ideas had just appeared in 1978, followed a decade later by The State and the Economic System (1989). Phyllis subtitled this later book as An Introduction to the History of Political Economy deliberately retaining the earlier description of the subject. This was not ideological, but simply to emphasise the “perennial political dimension”12 of economics in relation to society. She sought to:

“[S]ketch the development of economic knowledge over the past three hundred years with particular reference to the ways in which the broader context of moral,scientific, and political ideas or events have influenced successive economists’ vision of the operations of the changing economic system and their views of the scope for purposive State action to shape the process of change.” (ibid, p.vi)

This echoed what she had concluded in her Presidential Address to the Royal Economic Society in 1982.

“The lesson, it seems to me, that we should draw from the history of economic thought is that economists should resist the pressure to embrace a one-sided or restrictive consensus. There is no kind of economic truth which holds the key to fruitful analysis of all economic problems, no pure economic theory that is immune to changes in social values or current policy problems.”13

For her there was room for more than one progressive research programme at the same time, a pluralism of approaches and an open mind in the subsequent debate. This resonates with a modern day appetite from students for a more heterodox approach to economics teaching. For this address she had deliberately borrowed the title of John Neville Keynes’s 1890 book, and Keynes senior was to be the subject of her last book, The Life and Times of J. Neville Keynes: A Beacon in the Tempest (2001). Phyllis dedicated the book to her “Friend and Companion for Over Half a Century”, Joan Porter. Joan’s support was invaluable, they had originally set up home together to care for their widowed fathers. They continued to dispense warmth and hospitality to students and friends from Stukeley Close near Newnham for many years.

Phyllis Deane’s work is remembered at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research with its annual Deane-Stone Lecture, and more recently the library was renamed in her honour.

Deane, P (1965) The First Industrial Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harte, N. (2012) ‘Professor Phyllis Deane: Leading and influential figure in the field of economic history’ Independent, 30 September.

Deane, P. & Cole, W.A. (1962) British Economic Growth 1688–1959, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Feinstein, C.H. (1972) National Income, Expenditure and Output of the United Kingdom 1855-1965, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Matthews, R.C.O., Feinstein, C.H., & Odling-Smee, J.C. (1982) British Economic Growth, 1856–1973 , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

See Özgöde, O. (2020) 'Institutionalism in action: balancing the substantive imbalances of "the economy" through the veil of money' History of Political Economy April Vol.52 No.2 pp.307-39.

Stone, J.R.N, Rowe, D.A. et al (1954) The Measurement of Consumer’s Expenditure and Behaviour in the United Kingdom 1920-38 Vol I, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

See Macekura, S. (2018) “Phyllis Deane and the limits of national accounting” NIESR Blog, https://www.niesr.ac.uk/blog/phyllis-deane-and-limits-national-accounting

Deane, P. (1948) The Measurement of Colonial National Incomes: An Experiment , National Institute of Economic and Social Research, Occasional Papers XII, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.152-3.

See e.g. Deane, P.M. (1953) Colonial Social Accounting (The National Institute of Economic and Social Research, Economic and Social Studies XI) London & Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bortis, H, (2017) ‘Phyllis Deane (1918-2012)’ in Cord, R.A. (ed) The Palgrave Companion to Cambridge Economics, London: Palgrave Macmillan, p.874.

Deane, P. (1989) The State and the Economic System, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.v

Deane, P. (1983) ‘The Scope and Method of Economic Science’, Economic Journal, Vol.93, March:1-12, p.11.

Thanks for such an illuminating and interesting piece, Robert. She was clearly a brilliant scholar and teacher. ‘If a draft chapter could pass muster with Phyllis too, then surely it had to be OK’. Wonderful!